Quebec: Simulation of a hazardous goods railway accident in Estrie to prepare for the worst.

Reviewing the Lac-Mégantic disaster in 2013 and the consequences of the lack of safety culture in companies.

Although it borders the United States, Estrie is probably not the most well-known region of Quebec. However, we all know the town of Lac-Mégantic, whose population barely exceeds 6,000 inhabitants, because of the 2013 rail disaster that saw a freight train carrying hydrocarbons derail due to technical, human, and organizational errors, causing 47 fatalities.

Rail accident simulations in this region probably revive the specter of this catastrophe.

"Fire safety services, when responding to events, are always in offensive mode because there may be lives at stake. In the railway field when we intervene, we are always in defensive mode until we have obtained the information for the initial phase of the intervention," says Jean-Pierre Couture, an expert from the Canadian Railway Association.

The exercise that took place on Saturday will be repeated in two years, with a new scenario, to once again test the expertise of the first responders and ensure an optimal response in case of a real disaster.

For those unfamiliar with the Lac Mégantic catastrophe, here is a recap of the event.

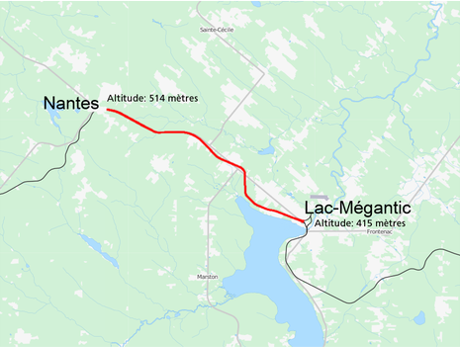

On June 5, 2013, the railroad engineer for the Montreal, Maine and Atlantic Railway (MMA) parked his train for the night in the town of Nantes (Quebec, not Loire-Atlantique, of course!). The train, consisting of 5 locomotives and 72 tank cars, was transporting about 8 million liters of crude oil from oil fields in North Dakota, USA. The cargo was then headed to refineries in New Brunswick.

When the engineer stopped the train, he left the main locomotive running, which maintained the air brake system. However, he only applied the handbrakes on the 5 locomotives and 2 tank cars, thus leaving the train inadequately secured on a downhill slope, before taking a taxi to sleep in a hotel in Lac-Mégantic. The rules stipulate that the handbrakes alone should be able to secure the train. The procedure thus requires a test to ensure this safety. The test was indeed conducted but included the air brakes. The engineer thus had the impression of leaving the train secure. Moreover, the engineer had mentioned to the local railroad controller that the main locomotive had had mechanical issues during the trip, notably emitting white and black smoke from the locomotive's chimney. The train was nonetheless left unattended on this track.

After the railroad engineer, the only personnel on board the train, left, a fire broke out in the main locomotive, where the engine is located. The firefighters then responded to the call, extinguished the fire, and then turned off the train's engine, in accordance with railroad instructions. When the firefighters left, the train's air brakes no longer functioned, the engine having been turned off. Just before 1 a.m. on July 6, 2013, the train slowly started moving towards the town of Lac-Mégantic, the handbrakes applied by the engineer no longer sufficient to stop it.

Reaching a maximum speed of over 100 km/h (65 miles/h), the train derailed near the center of Lac-Mégantic around 1:15 a.m. About 6 million liters of crude oil escaped from the 63 derailed and exploded tank cars, killing 47 people, forcing the evacuation of about 2,000 residents, and destroying a large part of the downtown area. About 100,000 liters of oil were spilled into the nearby Chaudière River, raising significant concerns about the consequences for waterways, wildlife, and downstream communities.

The majority of the victims were in the Musi-Café where the temperature during the explosion reached over 3000°C.

<img src="/files/music-cafe_4eeda5cd34bd0c1269783a800b45e87d

A unique communication solution at the service of businesses

A unique communication solution at the service of businesses